This week we’re happily putting 1,000+ copies of our new books in the mail to those who submitted to this year’s book contests. Thanks for trusting us with your work and we hope you enjoy these new collections. Tag us in a photo on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram for a chance to enter our raffle. Happy reading!

New books by Anna Maria Hong, Nicholas Gulig, & Shaelyn Smith

Our spring catalog is now available for purchase! Click the photo below to order new books of poetry by Anna Maria Hong and Nicholas Gulig as well as Shaelyn Smith's debut collection of essays. All titles are also available at Small Press Distribution.

Announcing the Inaugural Anisfield-Wolf Fellow in Publishing & Writing

The Cleveland State University Poetry Center & Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards are pleased to announce our first Fellow in Publishing & Writing. We're thrilled to welcome Leila to Cleveland and look forward to collaborating with her on future editorial, publishing, and outreach projects.

Leila Chatti is a Tunisian-American poet and author of the chapbooks Ebb (Akashic Books, New-Generation African Poets Series) and Tunsiya/Amrikiya, the 2017 Editors’ Selection from Bull City Press. She is the recipient of a grant from the Barbara Deming Memorial Fund, prizes from the Ploughshares’ Emerging Writer’s Contest, Narrative’s 30 Below Contest, and the Academy of American Poets, and fellowships and scholarships from the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, the Tin House Writers’ Workshop, the Key West Literary Seminar, Dickinson House, and the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing, where she is the 2017-2018 Ron Wallace Poetry Fellow. Her poems have appeared in Ploughshares, Tin House, The Georgia Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, New England Review, Kenyon Review Online, Narrative, The Rumpus, and elsewhere.

Anisfield-Wolf Fellowship in Writing & Publishing

JOB DESCRIPTION

The Cleveland State University Poetry Center is accepting applications for the Anisfield-Wolf Fellowship in Writing & Publishing, a two-year post-graduate fellowship that offers an emerging writer time to work toward a first or second book and an opportunity to gain experience in editing, publishing, literary programming, and outreach in collaboration with the staff of the CSU Poetry Center.

The CSU Poetry Center is a 55+-year-old independent nonprofit press that publishes 3–5 books of contemporary poetry, prose, and translation each year. The Poetry Center also hosts the Lighthouse Reading Series and serves as a teaching lab for undergraduate and graduate students at Cleveland State University and within the Northeast Ohio MFA program. The Fellow will be a two-year employee of the CSU English department. The salary is $40,000 per year with health insurance and benefits.

The fellowship will encompass two academic-year (9-month) residencies of 30 hours per week, divided between writing, work at the CSU Poetry Center, and an outreach project of the Fellow’s own design. Poetry Center work will include reviewing submissions, attending editorial meetings, and assisting with Center contests. Possible outreach projects include (but are not limited to): developing an anthology incorporating authors from an underrepresented community; organizing community writing workshops; developing a reading series to engage previously underserved communities; or working with a local organization involved in education, social justice, and the literary arts. The project should be designed and completed in the two years in which the Fellow is in residence. It is expected that this work will further engage an already enthusiastic writing community at Cleveland State University and throughout Cleveland. Additional professional development opportunities for the Fellow will include participation in Cleveland Book Week and public readings of their work for the Cleveland literary community.

This fellowship is named for and supported by the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards, which honor literature that promotes equity and social justice and are administered through the Cleveland Foundation. Through the creation of this fellowship, Anisfield-Wolf and the CSU Poetry Center hope to support writers from backgrounds and with perspectives historically underrepresented in publishing and creative writing programming. By providing editorial experience and opportunities at a literary press, the fellowship also aims to help address the longstanding lack of diversity in the U.S. publishing workforce.

CSU POETRY CENTER STAFF

Caryl Pagel, Director

Hilary Plum, Associate Director

ANISFIELD-WOLF FELLOWSHIP ADVISORY BOARD

Hayan Charara

Kima Jones

Janice Lee

Adrian Matejka

Prageeta Sharma

ABOUT ANISFIELD-WOLF

Cleveland poet and philanthropist Edith Anisfield Wolf established the book awards in 1935 in honor of her father, John Anisfield, and husband, Eugene Wolf, to reflect her family’s passion for social justice and the rich diversity of human cultures. Founded with a focus on combating racism in America, the Anisfield-Wolf Awards today maintain that commitment to equity and justice in an expanded, global context. Recent winners, for example, have also addressed religious identity, immigrant experiences, LGBTQ+ history, and the lives of people with disabilities.

MINIMUM QUALIFICATIONS

1. MFA in creative writing

2. Evidence of significant creative publication

3. Demonstrated progress toward a first or second book in any genre of creative writing

4. Strong interpersonal and communication skills

5. Outreach project proposal detailing the project’s mission, required resources, and preliminary plan/schedule

6. Potential to complete outreach project during the fellowship period

7. Ability to contribute to the diversity, cultural sensitivity, and excellence of CSU and its surrounding community

PREFERRED QUALIFICATIONS

1. Strong record of significant creative publication

2. Experience in arts engagement/outreach to underserved communities

3. Evidence of successful completion of community arts engagement/outreach projects

REQUIRED APPLICATION MATERIALS

1. Cover letter describing your qualifications for the fellowship, including a description of your commitment to a fellowship that supports increasing diversity in the publishing workforce

2. Preliminary project proposal (1–2 pgs)

Mission: Describe the project and what you hope it will achieve

Resources: What resources your project will require

Calendar: Proposed schedule over two years

3. Writing Sample (15–20 pgs max.), any genre of creative writing

4. CV

5. Names and contact information for three references

Submit application to CSU’s online applicant portal by February 1, 2018.

Finalists will be interviewed either by Skype or at the 2018 Association of Writers and Publishers Conference in Tampa (March 7–10, 2018).

End-of-Year Round Up

We’ve had a wonderful year at the Cleveland State University Poetry Center, and as the days get shorter and the air gets chillier, we’d like to bring you some of our most exciting news and updates. If you’re inspired by what you see below and would like to donate to our cause of publishing 3-5 collections of contemporary poetry, prose, and translation a year in addition to running The Lighthouse Reading Series and providing pedagogical and outreach opportunities for CSU students please know that your support is what allows us to continue publishing and programming throughout the year.

AUTHOR NEWS

James Allen Hall’s collection of essays, I Liked You Better Before I Knew You So Well, appeared on SPD’s bestsellers list; QNotes’ “Ideas for the LGBTQ book lovers on your holiday gift list;” and Anomalous Press’ “Books to Watch Out For.” Hall was interviewed by Alex DiFrancesco at the CSU Poetry Center blog and appeared on Woodstock Book Talk in October. Colorado Review says Hall handles fraught topics “deftly, with a sly sense of humor;” Newpages writes that “a collection of essays has never been so utterly tragic and full of truth;” and Queen Mob’s Tea House says I Liked You Better “takes the cool, intellectual quality of conceptual writing and poetics and turns it in on the self, allowing for experimentation while maintaining intimacy.” More can be found at American Microreviews, Reviews by Amos Lassen, Hunger Mountain, and The Rumpus.

In Entropy, Carrie Lorig writes of Jane Lewty’s second book, In One Form to Find Another, that “Lewty feels through the body’s ferocious, complex response to trauma while refusing to create a linearity and narrative arc which names or details the transgressive / traumatic event.” Lewty’s collection was named “Book of the Week” at the Volta and excerpts can be found at La Vague and Verse Daily.

Sheila McMullin’s first book of poetry, daughterrarium has been beautifully reviewed at Forward Reviews, Southern Indiana Review, Heavy Feather Review, Galatea Resurrects, and So To Speak, where Kristen Brida writes that, “McMullin focuses and reveals the many ways the feminine body is exploited, is overpowered in the patriarchal schema of the world.”

You can also find new books, poems, reviews, or interviews by Leora Fridman, Allison Titus, Lo Kwa Mei-en, Phil Metres, Dora Malech, Rebecca Gayle Howell, Zach Savich, Sandra Simonds, Elyse Fenton, Lee Upton, and Lily Hoang. Shane McCrae, author of Mule (CSU Poetry Center, 2010) ) was the winner of a Lannan Literary Award and a National Book Award finalist for his newest collection, In the Language of My Captor, published this year by Wesleyan.

CSU POETRY CENTER GRADUATE ASSISTANTSHIPS

The CSU Poetry Center offers graduate assistantships in small press editing and publishing for CSU-based students in the NEOMFA (Northeast Ohio Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing). If you or anyone you know is researching MFA programs in creative writing you might consider Cleveland State where we’re lucky to host the Lighthouse Reading Series, Playwrights Festival, and Whiskey Island Magazine, among other exciting writing programing. The NEOMFA is the nation's only consortial MFA program in the nation and boasts four schools’ worth of creative writing faculty and a great visiting writers series (this year includes CAConrad, Kelly Link, Emily Mitchell, Rob Handel, and Adam Gopnick). Application deadline: January 15th.

TRANSLATION SUBMISSIONS

The CSU Poetry Center invites queries regarding book-length volumes of poetry in translation for a new occasional series. Please send 1) A cover letter describing the project and confirming any necessary permissions; and 2) a sample translation of at least 20 pages. Full manuscripts are welcome. Email materials to associate director Hilary Plum at h.plum [at] csuohio [dot] edu. Submissions will be open until December 31, 2017.

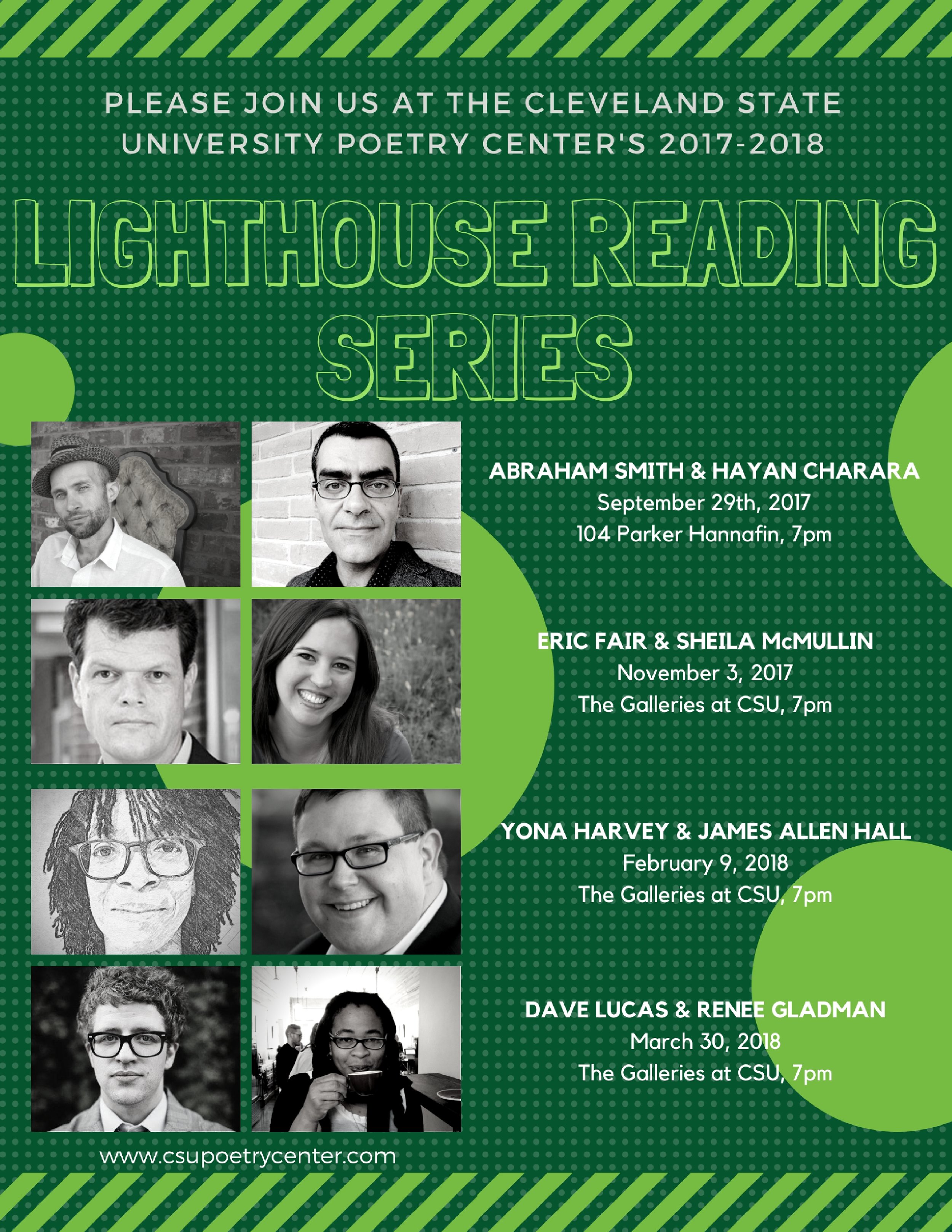

LIGHTHOUSE READING SERIES

This year’s Lighthouse Reading Series has hosted Abraham Smith, Hayan Charara, Sheila McMullin, and Eric Fair, all of whom absolutely blew our audiences (and us!) away. Spring readers include Yona Harvey and James Allen Hall (2/9/18), and Dave Lucas and Renee Gladman (3/30/18). If you live in Northeast Ohio, we hope to see you in the spring!

Book Interview: James Allen Hall & Alex DiFrancesco

Alex DiFrancesco: You’re an accomplished writer of both poetry and lyric essays. How do you feel the two overlap, and how do they differ? How does your process vary?

James Allen Hall: The essay is roomier and can accommodate a more disparate range of tones, so that the tragic and the comic inform and inflect one another. Essays come more piecemeal—it's like writing a suite of poems, or a crown of sonnets: each one approaching the subject from a different angle.

I think metaphor is where the poet and the essayist overlap. Trying to say the unsayable, to make shock familiar or familiar shocking. I like making other poetic elements—the compression of white space, the reverberating silence of the line break, burnished sonic texture, the structure of feeling—work for narrative's sake as well.

Poems use two compositional processes simultaneously: the line and the sentence. Nothing else can do that, talk with two mouths. It's why poetry endures.

AD: You’ve spoken in previous interviews about how you love the distance and closeness that metaphor allows a writer. Are there topics that are easier to write about in metaphor that we might not broach in conversation or less symbolic and lyrical writing? Do you write poems and essays you’d never be able to have a conversation about?

JAH: Metaphor can make it easier to touch a subject that is fraught or painful for the writer. It's a welder's mask or mitt. Sometimes I think it's a way of tricking the writer to get out of her or his or their own way and discover how we truly feel about complex subjects.

I often will talk about tough things with friends first, then try to form them into a poem or an essay. Sometimes I write both about a subject (for instance, being raped), and of course because form is a way of thinking, all of these are different. The conversation asks: can I be understood? Is there something I haven't seen yet? The poem has a different question: What is silence's role in what happened to me? The essay's question: How does this keep happening; how is this a social building block?

AD: A lot of your work is very personal. As a writer of such essays, where are the lines of what you feel is fair game for writing about and what you feel is not? How does the James Allen Hall on the written page differ from the James Allen Hall in the world?

JAH: The ethical aim is to treat people fairly—and to subject someone to no more investigation or excoriation than you would yourself. That said, some stories don't belong to you. In an essay called "In Lieu of Drugs," I discuss my brother's addiction and recovery, and the story of his "rock bottom" is one I feel I can't say. It's not mine to say. But, that story had its impact on me as well, and I needed to include it in the essay. I ended up using line and stanza break marks and large chunks of white space to mimic the gaps, the silences, the unknowingness and instability and brokenness of how I experienced that time. In other words, I won't tell his version of that story (what might be seen as his story), but I can tell the version of it as it unfolded to me. There's a way to write about other people.

I feel like my best self—the most honest about my flaws, the most emotionally intense part of me (the part of me I like best and am most embarrassed by since I don't know where it fits into the world) is on the page. The James Allen Hall in the world calls himself "Jamie," his given name that only intimates know. I try to as vulnerable in my life as I am on the page: maybe vulnerable isn't the right word. Maybe open. I think my blessing as a writer, and my curse as a person, is that I let in too much world.

AD: You’ve spoken previously about writing from the margins, but in a way that more people than those of your experience can access. What craft suggestions and tools do you have for writers looking to accomplish similar things?

JAH: I am in love with image so powerfully because of its ability to activate the limbic system in our brains, so that readers participate in the brick-and-mortar building of the worlds we describe. Metaphor, too, does this: makes the art participatory, genial, a gathering of minds for like-minded purpose. I think of Melanie Rae Thon's story, "Xmas, Jamaica Plain," in which Thon uses metaphor and image to introduce us to a character we may not like, or whose values we may not espouse. Image and metaphor create an immediate connection. I also think about point of view and tone—an "I" can create immediate connection as well, but not if its not perceived of as genuine, honest, and capable of beautiful and tense and surprising truths, all while incorporating some self-critical distance. Tone must be at odds with subject matter as well: since it is the way we perceive feeling, it needs to establish a voice's reasonableness or ethical stance before moving to the very emotional (there are of course exceptions). Craft remains paramount—no subject writes itself compellingly without craft.

AD: What are you working on now?

JAH: I am loving the way I can think in the essay right now. It feels adequate formally to respond to our moment. I'm writing a collection of essays, the core of which concern a particularly rough spate of time in which my grandmother died, my boyfriend broke up with me, my brother became an addict, my best friend was ousted from her job in our academic department, and I was suffering from suicidal ideation. You know. Happy stuff.

*

James Allen Hall is an associate professor of English at Washington College, where he also serves as Director of the Rose O'Neill Literary House. In April 2017, he published I Liked You Better Before I Knew You So Well, a book of lyric personal essays which won Cleveland State University Poetry Center's Essay Collection Competition, judged by Chris Kraus. Also a poet, Hall is the recipient of fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York Foundation of the Arts, the University of Arizona Poetry Center, and others. His first book of poems, Now You're the Enemy (University of Arkansas Press, 2008), won awards from the Lambda Literary Foundation, the Texas Institute of Letters, and the Fellowship of Southern Writers.

Poetry in Translation: Open Call

The CSU Poetry Center invites queries regarding book-length volumes of poetry in translation for a new occasional series. Please send 1) A cover letter describing the project and confirming any necessary permissions; and 2) a sample translation of at least 20 pages. Full manuscripts are welcome. Please email materials to associate director Hilary Plum at h.plum [at] csuohio [dot] edu. Submissions will be open until December 31, 2017.

Lighthouse Reading Series 2017-2018

Summer Celebrations

SUMMER CELEBRATIONS

Join us in celebrating our 2017 catalog, recent contest winners, author news, and reviews. If you'd like to review, teach, or host a reading for one of our authors, contact us at poetrycenter@csuohio.edu for more information.

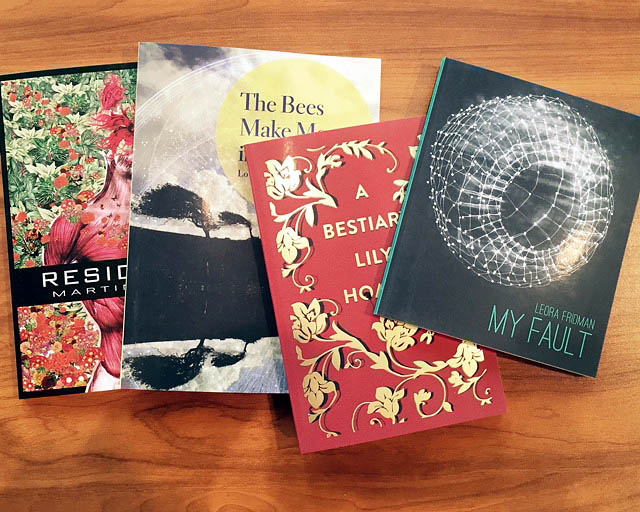

Lily Hoang's essay collection A Bestiary is a finalist for PEN Center USA's Literary Awards in Creative Nonfiction.

Martin Rock, author of Residuum, will be included in 2018's Best American Experimental Writing.

Lo Kwa Mei-en, author of Bees Make Money in the Lion, is a finalist for the Poetry Foundation's Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Fellowships.

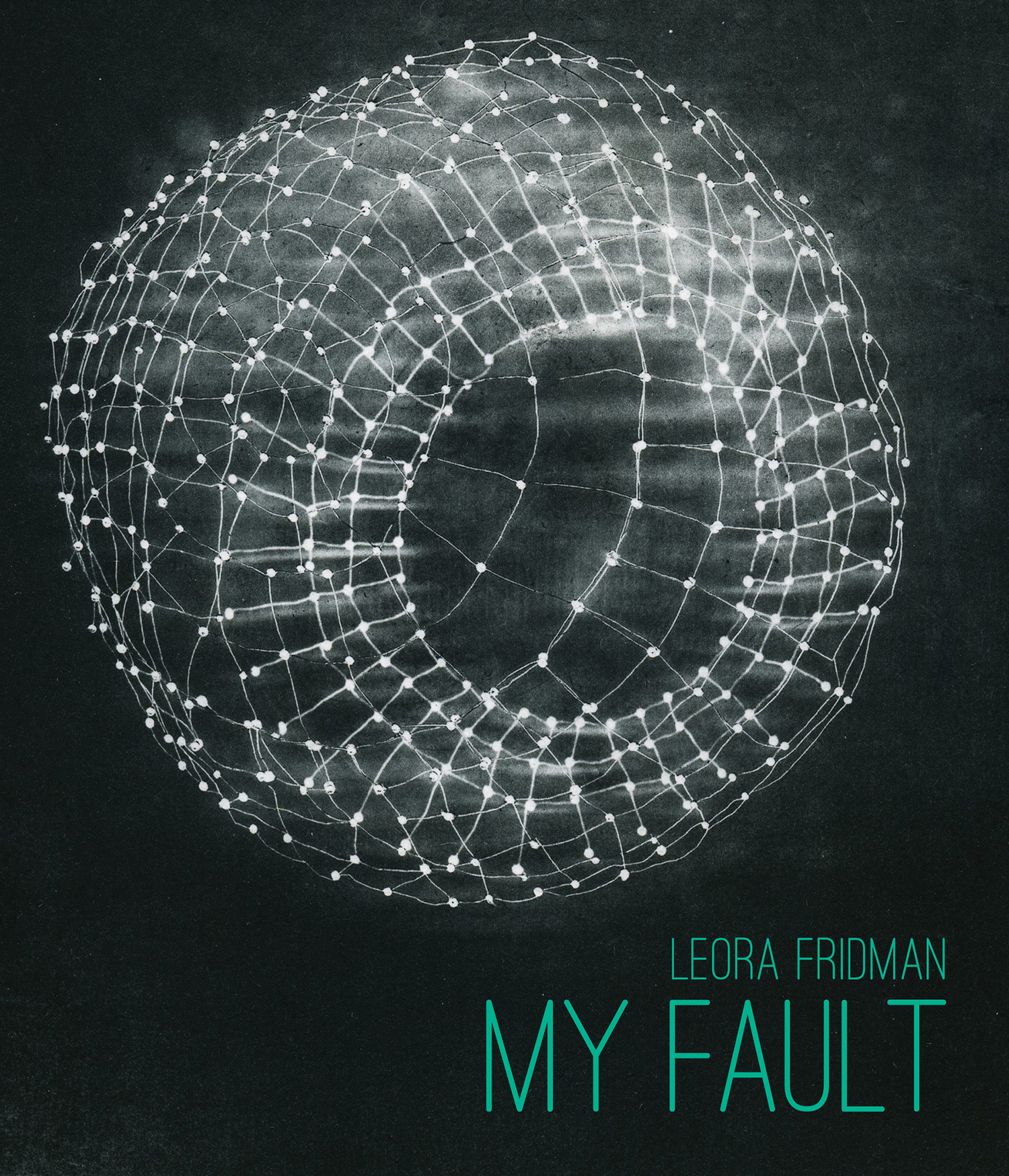

Leora Fridman, author of My Fault, has new prose at The Rumpus, Temporary Art Review, and Pacific Standard.

Congratulations to the winners of our annual book contests — Anna Maria Hong, Nicholas Gulig, & Shaelyn Smith — whose books are forthcoming Spring 2018.

NEW BOOK NEWS

Sheila McMullin's daughterrarium

Reviewed at Galatea Resurrects.

Reviewed at Heavy Feathers Review.

Reviewed at Foreward Reviews.

Jane Lewty's In One Form to Find Another

Reviewed at Entropy.

Book of the Week at The Volta.

Excerpt at Verse Daily.

James Allen Hall's I Liked You Better Before I Knew You So Well

Reviewed at Colorado Review.

Reviewed at NewPages.

Reviewed at Queen Mob's Teahouse.

Interview at The Rumpus.

SPD's Bestsellers List / Nonfiction.

2017 Book Contest Results

The CSU Poetry Center is excited to announce the results of our 2017 book competitions. The following three books were selected from nearly 1,200 manuscripts and will be published in spring 2018. Thank you to everyone who sent us work & congratulations to the writers below.

Winner of the First Book Poetry Competition

Judge: Suzanne Buffam

Anna Maria Hong: The Glass Age

Anna Maria Hong is the Visiting Creative Writer at Ursinus College, where she teaches poetry, fiction, and hybrid-genre writing. A former Bunting Fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, she has published fiction and poetry in The Nation, Poetry, Ecotone, POOL, Southwest Review, Fence, Best New Poets, The Best American Poetry, and Verse Daily, among other journals and anthologies. Her poetry chapbook Hello, virtuoso! was published by the Belladonna* Collaborative and her novella, H & G, won the inaugural Clarissa Dalloway Prize from the A Room of Her Own Foundation and will be published by Sidebrow Books in early 2018.

First Book Honorable Mentions: Megin Jimenez’s Lone Stories; Melissa Barrett’s Moon on Roam.

First Book Finalists: Bryan Beck’s Countryman; Emily Brandt’s ManWorld; Ashley Chambers’s The Exquisite Buoyancies: A Sonography; Ansley Clark’s Bloodline; Samuel Corfman’s Luxury, Blue Lace; Scott Cunningham’s Ya Te Veo; Binswanger Friedman’s The Four Color Problem; Pamela Hart’s Mothers over Nangarha; Amelia Klein’s Brilliant Dust; Davy Knittle’s get on like houses; Christine Larusso’s Mar; Rebecca Liu’s Mutter Tongue; Anna Mebel’s The Princess of Animals Invents Loneliness; Soham Patel’s ever really hear it; Nicholas Regiacorte’s American Massif; Robert Yerachmiel Snyderman’s Deform; Bronwen Tate’s Probable Garden; Candice Wuehle’s FIDELITORIA: fixed or fluxed.

First Book Semi-Finalists: Robyn Anspach’s Samson Speaks of Darkness; Micah Bateman’s Civil Servants; Timothy DeMay’s Avenue; Jonathan Dubow’s The Booth; Katherine Factor’s A Sybil Society; Judith Huang’s You, Riverine; Kimberly Kruge’s In-Migration; Megan Leonard’s What Queen What Binary Star; Paige Lewis’s No More; Jessica Marsh’s The Long Modify; Kelly Nelson’s The Possibility of My Absence; Michael Peterson’s Repeater; Cherry Pickman’s Islanders; Lacy Schutz’s Meathead in America; Bret Shepard’s Living As Magnets; Dennis James Sweeney’s In the Antarctic Circle; Grey Vild’s Ain’t Never; Sara Wainscott’s Insecurity System.

Winner of the Open Book Poetry Competition

Judges: Rebecca Gayle Howell, Lo Kwa Mei-en, & Lee Upton

Nicholas Gulig’s Orient

Nicholas Gulig is a Thai-American poet from Wisconsin. The author of North of Order (YesYes Books) and Book of Lake (Cutbank), he currently lives in Fort Atkinson, WI and teaches at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater.

Open Book Finalists: Samuel Ace’s Our Weather Our Sea; Sarah Boyer’s Righteous, Chrillis, My Mimi, & The Owl; Caroline Cabrera’s (Lack begins as a tiny rumble); Kristen Case’s Principles of Economics; Lorene Delany-Ullman’s Souvenir; Brandi George’s Faun; M.C. Hyland’s The End; Krystal Languell’s Quite Apart; Michelle Lin’s The Year of the Horse is Dead; Kristi Maxwell’s Bright and Hurtless; Alexis Pope’s That Which Comes After; Michael Robins’s With Love, Etc.; Kent Shaw’s Too Numerous; S.A. Stepanek’s somebody, maybe: a love poem; Terese Svoboda’s 40 Days/Nights; Gale Thompson’s Expeditions to the Polar Seas; Daneen Wardrop’s Catch My + Slips So Easy.

Open Book Semi-Finalists: Geoff Bouvier’s Potential Soldier; Lisa Fay Coutley’s Tether; Dot Devota’s By Abundant Delinquencies; Michael Tod Edgerton’s Yet Sensate Light; Stevie Edwards’s Lush; Laura Eve Engel’s I Write To You From the Sea; Henry Israeli’s Notes Toward a Revolution; Jason Koo’s More Than Mere Light; Dora Maelch’s Stet; Beth Marzoni’s There Was During a Sudden; Alexis Orgera’s Monster, Fall; Meghan Privitello’s One God at a Time; Alicia Rabins’s Fruit Geode; Mara Adamitz Scrupe’s & Bless The Survivors; Purvi Shah’s Miracle Marks; Jon Thompson’s Notebook of Last Things; Andrew Wessels’s The Sunshiny Field.

Winner of the Essay Collection Competition

Judge: Renee Gladman

Shaelyn Smith: The Leftovers

Shaelyn Smith grew up in northern Michigan, and received an M.F.A. in nonfiction from the University of Alabama. She now lives in Auburn, AL. Her work can be found in Essay Daily, storySouth, Sonora Review, The Rumpus, and Forklift, OH.

Essay Collection Finalists: Jennifer Militello’s Knock Wood; Addie Tsai’s and in its place--: An Ode to Frankenstein; Laurie Blauner’s I Was One of My Memories; Diana Arterian’s Arrangement of Parts; Kisha Schlegel’s Fear Icons; Joshua Bernstein’s In Josaphat’s Valley; Toni Mirosevich’s Spell Heaven; Beth Peterson’s Theory of World Ice; Sarah Minor’s At Home With River Animals; Sejal Shah’s Things People Say.

Essay Collection Semi-Finalists: Julie Marie Wade’s The Hourglass; Charles Green’s Ways of Being Afraid; Noah Eli Gordon’s Dysgraphia; Krista Eastman’s The Painted Forest; Frank Light’s Far and Away; Michael Levan’s Gravidarum; Matthew Schultz’s Other Places; Jill Darling’s The Collateral Media Project; Brenda Iijima’s End Empire, Apparition On; Rachel Peckham’s The Aviatrix.

2017 SPRING CATALOG

Our spring catalog is now available for purchase! Click the photo below to order new books of poetry by Sheila McMullin and Jane Lewty as well as James Allen Hall's debut collection of essays. All titles are also available at Small Press Distribution.

Book Interview: Lily Hoang & Scott Krave

Scott Krave: Throughout the book there are recurrences of mythological images and retellings of those stories. You "have tangled the fairy tales [you] write with [your] life." What drew you in that direction?

Lily Hoang: I understand the world through fairy tales. I often say that I spend 50% of my life toiling and 50% of my life marveling. My ability to marvel is also my devotion to the marvelous, to the fairy tale. It only makes sense, then, that my non-fiction essays fold fairy tale and myth as a lens to understand the real—whatever the real even means because it’s a term that fully eludes me.

SK: Our society's scientists threaten rats with drowning, tempt them with addiction, gage their loneliness. Where do you see the line, if there is one at all, between instinct and social conditioning? What is it about rats and the tests they undergo that speaks to you so much?

LH: Quite honestly, my interest in rats had to do with the necessity of talking about rats for the Year of the Rat. Rats and psychology experiments weren’t part of the first incarnation of this essay at all though. I completely rethought the essay when I was given the opportunity to revise the book. The original essay was called “On Captivity and Rats,” and it had much more to do with imprisonment (of people, not rats). When I re-titled and re-conceptualized the essay as “On the Rat Race,” I naturally thought of rats and experiments. I wanted to talk about rats in maze boxes, and through research (and an obscene amount of research, too, I might add), I found many more apt experiments for the essay, such as the Morris water maze. And I say this in “On Scale,” but when I re-connected with my college obsession Jacob, who’s now a forensic neuropsychologist, I wanted to impress him with my rat knowledge, but then he taught me so much more about how rats are used with addiction research, which served as perfect foil to my nephew’s heroin addiction. So whereas it wasn’t coincidence, per se, it was maybe more fate—not in a religious way, more of in the inevitable way of magic stories. Perhaps, then, I am obliquely answering instinct v. social conditioning and saying social condition began the process with “On Captivity and Rats” and instinct took me to “On the Rat Race,” to the sorrow and loneliness of addiction and loneliness.

SK: Many portions of the book are temporally fluid, moving from point to point with little regard for linearity of narrative. What about this stylistic choice helped you to create your desired mood?

LH: It’s funny because I get permutations on this question all the time, and I always think of it as a process question so I’ll answer it in those terms (I hope you don’t mind). I wrote the book how I did because it’s the only way I know how to write. My brain moves in little pieces that connect via unpredictable routes to make a greater whole. A question I often frames my style as a whole that is broken into pieces and scattered around—almost as if haphazardly or accidentally re-ordered—but the essays come out as you read them. Every piece is intentional, insofar as that’s the way the essay comes to form in my brain. It’s the only way I know how to understand things.

SK: What are you working on next?

LH: I’m currently revising—re-writing—a novel I’ve been writing for the past decade. It’s based on a true story of a woman who rolled over her four children with the bulk of her 250 pound body as punishment and revenge on her husband for fighting with her. The novel attempts to force you to empathize with the serial killer—it humanizes her to an almost painful limit—only to slap you in the face with her undeniable monstrosity.

***

Lily Hoang is the author of five books, including A Bestiary (winner of the Cleveland State University Poetry Center’s inaugural Essay Collection Competition) and Changing (recipient of a PEN Open Books Award). With Joshua Marie Wilkinson, she edited the anthology The Force of What’s Possible: Writers on Accessibility and the Avant-Garde. She is Director of the MFA program at New Mexico State University and serves as an Editor at Puerto del Sol and for Jaded Ibis Press.

AWP 2017: Washington DC

Join the Cleveland State University Poetry Center and Rescue Press for an AWP offsite book launch and reading. Our presses believe in the future of books and the necessity for innovative literature; we're thrilled to spend an evening celebrating new poetry and prose.

Our event will take place from 7-9 p.m. on Thursday, February 9th at The Black Squirrel, a gastropub in Adams Morgan (Washington, DC).

Readers will include:

Vanessa Jimenez Gabb

James Allen Hall

Douglas Kearney

Andrea Lawlor

Jane Lewty

Sheila McMullin

Hilary Plum

Adrienne Raphel

Zach Savich

We'll have pre-release copies of our 2017 spring catalogue available for purchase throughout the weekend; if you can't make it to the launch reading, stop by our table at the AWP Conference book-fair (#616-T). See you in DC!!

Book Interview: Leora Fridman & Brandon North

Brandon North: My Fault is comprised of several different kinds of poems. There are poems in couplets, iterations of free verse, a prose poem, poems in a single stanza block, and the first poem, “Grown to Covet,” has some fairly loud rhymes right as the reader dives in. Could you say a little about why the different forms of poems are important in My Fault? And do the collection’s opening lines—“I am most myself when watching / a stranger hit my hand”—indicate something to a reader about using different poetic forms as a way to examine many types of interactions between the self and others?

Leora Fridman: I think the different kinds of poems in My Fault point to a fairly common story about first books — that most are much more a collection than they are in any way a “project.” My Fault came together in a moment of frustration with an earlier manuscript, a manuscript that was one long poem and that I’d been sending out for two years to lots of great but inconclusive finalist-ing. Instead of sending that one out again, I decided to rip apart of lot of the poems I’d written the previous 3-4 years and put them back together, and thus was made My Fault.

For that reason the book is really a “collection” in the sense of collecting many different times and strategies and attempts, but is united by my interests and obsessions over a certain period of time.

To answer your second question, yes, definitely, this is a book about interaction and missed interaction, failed and flubbed interaction, desired interaction, despised interaction. So yes, to some degree the different forms correspond to different moods I have about what it means to be an individual self interacting with others. I chose to start the collection with a more rhyme-y poem because I find rhyme inviting and calming, a linking back into a comforting nursery-rhyme-ish culture that I can dip into and can seek protection in. So I started there, and I intersperse rhyme (or sound echoes, more precisely) purposefully throughout the book to beckon the reader in more kindly, especially in moments when I think they might be getting confused or scared or distracted or alienated… I mean, I want some of those feelings to happen — the alienation etc — but I’m not personally invested in complete alienation of the reader in these poems. There’s a wave in and out of the more and less comforting.

So the ordering of types of poems in the book definitely has to do with me trying to dip into and out of different kinds of alienation, familiarity, standoffishness, intimacy… not promising that one of those things will last the whole book or that just because I have offered one of those things it will exist into the complete ongoing future. I was just talking last night in Atlanta with Katherine J Lee and Carrie Lorig about multiplicity of emotions — what it means to create a world in which multiple emotions / experiences are actually allowed in one person, and in which one person is not stuck forever in one emotion just because they are having it. I am especially interested in the ways in which people socialized as female are often taught that once we offer intimacy or closeness or welcome or empathy we have to keep offering it even if it becomes uncomfortable or dangerous for us — or even if it just becomes something we no longer want to do. I’m interested in what we can achieve by creating situations (linguistically, poetically) where intimacy exists in small contained glimpses and then goes away, and that is allowed and okay. That makes me feel safe, and boundaried, and in charge of my own body / experience / narrative. Which yes, for me, is all connected to there being many different kinds of poems in this book…

BN: Though several types of poems do appear in My Fault, more often than not the poems employ shorter, fragmented lines with little to no punctuation. Could you discuss why this approach works with the content of your poems? Is there a connection, for example, between how the short lines of the poems take up time and space across pages and how they also produce an effect of cautiousness, or even trepidation, for the reader?

LF: Hm, that’s an interesting interpretation! Ha, yes, I would say trepidation and caution are in the book, for sure. I wouldn’t say the shortness of the lines is related in a linear fashion to an amount of trepidation a speaker is feeling, but I would say they’re intended to evoke trying to piece action and language together in an ethical fashion, and the pause that creates in a mind, the patchwork.

My friend Emily was trying to learn to cook and she would play this game for us where she’d perform a cooking show starring “The Cautious Cook.” She do a great Julia Child voice. She’d pick up an onion and look up, confused. How shall I cut it? She’d say, and wait for an answer. Then, what knife shall I use? Once she got the knife, she’d ask how she was supposed to hold it, how big “chopped” meant. Etc. But this was all real for her. Each step of the process was something she wasn’t sure how to do.

And that jerkiness of caution is in this book. (Not about cooking, but about other things.) The voice in the book is definitely trying to do right — do right by any number of ethical, environmental, gendered approaches — and wants to take its time doing right, understanding right. But at the same time it wants to rush forward, go fast, speak passionately and not care what others think of its formulations… it’s a gushing that cuts itself off.

Another thought: because I enjoy so much the hinge of the stanza and the hinge from fragmented phrase to the next — the insecurity that can happen there, the way one word can turn quickly from one meaning to another because of the stanza break — I also get a lot of pure joy out of working with short lines. I feel I can winnow down to the smallest hitches of meaning and build us back up from there.

One last attempt: I want to pare things back to make room for multiplicity — to provide juuuuust enough structure for the reader to feel safe / on the edge of safe / safe enough to experiment / imagine / place the poem in their own context. Just enough structure that people feel safe enough to imagine their way in. I remember seeing in movies how at Catholic school dances they would tell people not to dance too close during slow dances — to “leave room for Jesus,” or “leave room for the holy ghost,” or something like that. That’s kind of how I picture this — leaving gaps / space so there is room for something meaningful / connected / your own to rush in — so I don’t force your mind in a certain / totally obvious direction, but rather leave space.

BN: On the Poetry Society of America’s website, you write: “I'm variously and always obsessed with blame and responsibility: how to take responsibility, how to blame and forgive, who is responsible for whom, etc. Fault itself is a mathematics, a system for understanding where we stand.” This insightful notion that fault is mathematical implies that measuring fault is not only pervasive—we analyze behaviors all the time—but also that it is a symbolic system which corresponds to real human actions. Could you discuss how the poems in My Fault are informed by the symbolic transfer of blame and responsibility, whether by assigning or removing fault? Are your poems, for example, animated by the notion of a call-out culture, what with the last lines of the book being “I went for the blaming / & found there more embrace”?

LF: Nail on the head for that last bit, yes. Calling-out and calling-in is so much all around me now, and I’m a proponent of both of those moves in different situations depending on the context and depending on the power dynamics. Those last lines also specifically point at the ways I’ve come to identify as a white person with extensive privilege in movement spaces, and how I’ve come to understand that privilege is not a blame game, but rather a way to place ourselves in a larger system — once I came to understand the workings of my own privilege, I found myself more connected, more willing to act, and, yes, even more empowered — to use that word — to move in the world in a more kind, free fashion, more aligned with the liberation of more people.

My Fault has no intention of removing blame from any one party or assigning blame to any one party in particular. Instead it intends to open the conversation about how we assign responsibility and how slippery it can be. I do not mean to say, for example, that historical oppression is to be deigned “slippery” and overlooked. It’s important to me that that not be misunderstood. I’m looking instead to a voice and a way of speaking that notices how fault is passed down and around — that fault is an exchange system and not one we (usually) get paid to handle, labor under or examine.

When I was on tour this past summer I started every reading with an participatory ritual / activity where audience members told one another their faults in a telephone-like fashion, and faults traveled across the room to be spoken at the end by someone completely disconnected from the person who first voiced them. It felt somewhere between the relief of confession and the deviousness of “two truths and a lie.” Both of these feels are in My Fault.

BN: In Dorothea’s Lasky’s essay-chapbook, Poetry is Not a Project, she questions using the word project to describe a poet’s work, maintaining that poets “intuit” poems and do not construct them so linearly as a scientist might conduct an experiment. Rather than a “project,” she states that “Real poetry is a party, a wild party, a party where anything might happen. A party from which you might never return home. Poetry has everything to do with existing in a realm of uncertainty.” In the uncertain (to the say least) political environment we now find ourselves in, what role can a poet have in relation to everyday realities? More generally: how do you approach political issues in your poems, especially in regards to the notion of writing-as-project?

LF: Great question! I so appreciate Dottie’s thinking about a project — even as I am a writer who primarily writes book length / serial poems that build on themselves. Even these, the building monsters that they are, work intuitively — I don’t know what’s going to happen with them when I start, so they grow rhizomatically, as my friend Ellie recently suggested to me, one lump creating another lump’s possibility.

Speaking of growth and lumps: politics, yes. Politics and my involvement in movement spaces related to gender, racial and economic justice are important to me. And now, this month, this fall, I offer thanks that they seem more important to all us, even those of us who wouldn’t call ourselves political at all a few months ago.

At 8 am the morning after the election I skyped into Jessica Bozek’s class in Boston to talk about My Fault. It was 8 am in California and I was emotionally hungover as all hell. The second before the call connected all I could think about was that this was the worst possible thing I could be doing right that moment. I felt trampled.

But the call started, and the students asked about abstraction and liberated language and politics and freedom, and it turned out that poetry, as I should well have known, always has some way it can help us in these moments. I shared with them how strongly I feel that the minute one breaks up traditional ways of speaking and understanding one is making room for non-normative language, non-normative thinking — making room for the mind to tweak and squeak its way out of the ways it is used to thinking… and that is by definition a political act. It’s essential to civic engagement that we think for ourselves, for our communities, that we try to tune into our own needs and the ways they intersect with the needs of others living close around us.

I also spoke with those same students about associative logic — the poems in My Fault work, in most cases, “associatively,” meaning that they move the way my mind moves, they move from one image or word to another because that is the jump that happens in my brain. I think it’s a political act to make public this kind of “internal” associative logic, because when we make them public we presuppose that our internal life is important to the communal, that there are ways of expressing ourselves / our opinions without offering propaganda. I see so many writers and artists shy away from creating explicitly political work because it feels like propaganda – but these last few weeks I’ve seen a dramatic shift there, like there’s nothing to lose suddenly, so folks are letting it out.

Cecilia Vicuña writes, “Life regenerates in the dark. Maybe the dark will become the source of light.”

I think there’s a tremendous place for poetry right now — people are asking for it, emailing it around, reading it in public, etc. A moment of crisis for many of us, and so we turn to broken language, language with gaps, language that attempts to understand without complete enclosing or convincing or proving something to us. Open language — here, I mean poetry, I suppose, though sometimes prose does it, too — helps us understand but still lets us stay alive, not locked up entirely in an external understanding but held squirmily, held, held.

BN: What are you working on right now?

Right now I’m working on a collection of nonfiction, a book of essays about care and loyalty. The book seeks to examine what it means to give and receive care — seeks to understand what we really owe one another. It looks beyond our divisive political conversations about progressivism vs “family values” towards actual interdependence and what it means to stick together. The book begins at a history of the term “self-care” cut again family stories of illness and alcoholism. It goes on from there to look at multiple shapes of family and caregiving networks vis-à-vis immigrant family, Black Lives Matter, radical queer community in gentrifying American cities, and more. I’m working with citations from care-workers and theorists and poets (always poets) alongside personal narrative to explore care from multiple angles including dependency, when care becomes abusive, and how we measure devotion. An adapted section of the book was published recently in Pacific Standard here.

I used to write a lot of prose and I haven’t, so much, in a while. It’s hard. It’s hard to figure out how I want these sentences to work / wander.

BN: Do you have any advice for young poets and writers?

LF: Just this past weekend I read at Emory University and we did a Q&A with students before the reading, students who asked all sorts of sweet questions that I loved that most “grown up” writers are too embarrassed to ask but definitely should be asking.

One of the questions a student asked was “how do you know when something is done?” but not just in the sense of tweaking it, in the workshop sense — it seemed she was struggling a lot with how to integrate the comments and edits of her teachers and fellow students vs. know when she had arrived at a place with a poem that felt meaningful / contained /completed in some way, to her.

I told her that I really think this is about attunement — that like anything in life you have to tune in to what you yourself are really trying to say / what really tunes onto your frequency and feels right inside your instrument. You’re never really going to feel done (completely) writing something, I think, so the best you can do is tune into when you have a feeling of satisfaction, delivery of something gut-like, when you are speaking in a way that means something to you. When poetry is working beautifully and bravely it has something to say that no one else can say in precisely that way. So no one can really tell you when you’ve done it but you and your close attunement.

Vicuña again: “Awareness is the only creative force that creates itself as it looks at itself.”

I guess related to that another piece of advice I always try to impart to students is try not to be embarrassed to ask the “dumb question.” Someone will probably be thankful you asked it, and your vulnerability opens up space for new knowledge, new ways of thinking that we are too easily closed off from in spaces where we are trying to look smart, able, literary in certain ways. I say look for the dumb question and poke it out into the light.

***

Leora Fridman is an interdisciplinary artist, organizer, and educator living in California. She is the author of My Fault, selected by Eileen Myles for the 2015 CSU Poetry Center First Book Poetry Competition in addition to three chapbooks of poetry, prose, and translations.

Lighthouse Reading + Open House (Friday, December 2nd, 2016)

Both events are free and open to the public; RSVP here.

Fall 2016 Catalog News

Thank you, dear readers, for your generous and thoughtful responses to our spring 2016 titles including reviews of Lily Hoang’s A Bestiary—our very first collection of nonfiction—at Publishers Weekly, Small Press Book Review, 3AM Magazine, Angel City Review, Full Stop, AsianAmLitFans, Winter Tangerine, the Ploughshares blog, Heavy Feather Review, Barrelhouse, and ZYZZYVA. A Bestiary has appeared at the top of SPD’s nonfiction bestsellers list for the past six months and interviews with Lily Hoang can be found at Late Night Library, Brazos Bookstore, The Conversant, and Essay Press.

Leora Fridman’s debut collection of poetry, My Fault, has been featured or reviewed at Publishers Weekly, Mass Poetry, Poetry Society of America, Small Press Book Review, Litseen, and Tell Tell Poetry.

Praise for Martin Rock’s Residuum appears at Fanzine, Transart Triennale, and Essay Press. Upcoming readings and events can be found here.

New poems, interviews, or reviews of Lo Kwa Mei-en’s The Bees Make Money in the Lion can be found at Publishers Weekly, Poets & Writers, Heavy Feather Review, Public Pool, and at our own blog with NEOMFA student Emily Troia.

*

We’re hard at work on our 2017 catalog which will include:

Sheila McMullin’s daughterrarium

Winner of the 2016 First Book Poetry Competition

Selected by Danile Borzutzky

Jane Lewty’s In One Form to Find Another

Winner of the 2016 Open Book Poetry Competition

Selected by Emily Kendal Frey, Siwar Masannat, & Jon Woodward

James Allen Hall’s I Liked You Better Before I Knew You So Well

Winner of the 2016 Essay Collection Competition

Selected by Chris Kraus

*

If you live in Cleveland, we hope to see you at this year’s Lighthouse Reading Series and in our new space on the 4th floor of the Michael Schwartz Library (Rhodes Tower) in downtown Cleveland.

Thanks to our NEOMFA students and Poetry Center staff for keeping this magnificent literary machine in motion.

Follow us on Facebook or Twitter for news throughout the year.

Book Interview: Lo Kwa Mei-en & Emily Troia

Emily Troia: In The Bees Make Money in the Lion, you play with several poetic forms—especially the abecedarian. What made you choose the abecedarian as a principle form?

Lo Kwa Mei-en: “The Alien Crown” was the most crucial series of poems for me, and the most demanding. The series’ constraints borrow from the abecedarian, the sonnet, and the sonnet crown, and for half a year I floundered in frustration that I could not “master” the form I was obsessed with. A direct result of the flailing was my understanding that the systemic constraints I had been so attracted to in the full range of these poems were guiding me within the larger themes of the work. Once I had reframed my relationship to the form, the work took on its own liveliness and seemed to make unusual, provocative, meaningful demands of me. The abecedarian form I used demands both rule-based, pre-ordained conclusions and ethical dedication to sensual, whole-hearted inquiry. For me, this paradox clarified something unspeakable about a lifetime’s worth of struggling at the crossroads of repression, violence, and creative energy. I think the double-sided abecedarian form is a way into experience. It is a cave that will change your voice. It is in and of itself the way I feel about many things. It made itself central to the book.

The primary texts of inspiration that led to my curiosity about abecedarianism were Inger Christensen's book Alphabet, Jasmine Dreame Wagner's book Rewilding, and Rebecca Hazelton's poem "Both Sides".

ET: Even though you strictly adhere to the forms you employ in The Bees, the writing never feels cramped or limited by them. Do you have any recommendations for other poets on how to use the constraints of form without becoming mired in them?

LKM: If there is a way to use the constraints of form without becoming mired in them, I would love to learn about it! I suppose one way is to only work with constraints that demand little to no real effort of you as an artist. But if you are working with formal constraint in an effort to grow artistically/personally, then I think becoming enmired, and spending considerable time in that place, is a valuable and unavoidable experience.

Maybe one practical suggestion is to consider the myriad possibilities that your formal constraint contains, to spend more time exploring its dynamic potential than you do trying to “get it right.” I don’t know that this is a great writing tip, but it’s key to the pleasure I found in developing my relationship to form.

Also, do not ignore your relationship to the formal constraints at work in literature that reach beyond the rules of, for instance, what makes a sonnet. I’m talking about how white supremacy, for example, shapes the canon and therefore our poetic education and therefore the distribution of resources and power in the publishing industry and therefore the authors that are most visible and likely to be read and therefore the state in which we ourselves approach the blank page. One of the most meaningful questions we can ask ourselves as poets is how we relate to the constraints of social inequity. Creativity within constraint is in large part about drawing new connections we had not seen before, and resisting the impulse to capitalize on the easiest proferred solution when we feel that we are enmired. I think that this is also an example of valuable and unavoidable work for artists.

ET: The Bees is in five parts but has elements braided throughout the entire book. Can you share a little bit about your process in structuring the manuscript?

LKM: The Bees Make Money in the Lion used to be in three parts. One section for all the poems that I titled “The Romances,” one for the Babel series, and one for the abecedarians, which I thought of as the science fiction section. I did this in part to bridge the different formal lens, and in part to close with the abecedarians, but at the end of the day, this structure bothered me. Its framing felt like a showcasing of formal technique and I was afraid that the story elements that resonate between the different voicings and tones would get lost. In addition, the “Okay, you’ve seen all there is to see of that; now come look at this” rhythm felt suggestive of a tourism narrative. In my first structural revision, I split both the first and third section into unresolved halves, so that there is the necessity return to as well as leave behind the different worlds I portrayed. (If someone is reading the book from beginning to end, that is.)

The book’s structure also echoes the double-ended constraints that are so prevalent in the poems, and this felt very right to me, as did Caryl Pagel’s idea to edit the second and fourth sections down to six poems each. One of my secret-ish goals for this book was to embrace the nature of formula. The interconnected lives of (social) bees are incredibly formulaic, and yet bees are one of the wildest subjects in the world, in my opinion. I wanted to see if I could submit my will to the formulaic aspects of poetry and still make something that sang with a voice of its own.

ET: In Audre Lorde’s essay “Poetry is Not a Luxury,” she writes, “The quality of light by which we scrutinize our lives has direct bearing upon the product which we live, and upon the changes which we hope to bring about through those lives. It is within this light that we form those ideas by which we pursue our magic and make it realized.” How would you describe the “light” in The Bees?

LKM: The light in The Bees Make Money in the Lion is almost audible in its insistence that it has the right to exist, and to exist without restraint, no matter the constraints of its environment. The light cannot avoid the violence that exists inside as well as outside its burning.

ET: What are you working on right now?

LKM: I’ve been working primarily on my health. The Bees Make Money in the Lion is without a doubt the last book I will have been able to write while compromising the work of taking care of myself—and if I’m honest about it, the book was only half-written in carelessness. (The first draft was completed while I was still drinking, and the revision process occurred after I had stopped.) This has been the first year that I have been able to commit to a widening range of “basic” health practices while also working multiple jobs.

In terms of writing, I have several books on deck, including the first book of an epic fantasy trilogy in poetry about the character Pinnochia and a science fiction novella about addiction, emigration, and love. But I haven't progressed in either of these works for a while. This year, I had to start over in the most foundational areas of my writing life. I am tragically results-oriented, so even the concept of experience being its own reward is in danger of being exploited by my ego: perhaps what I need to let go of is the idea of the reward at all.

As a result, I've been prioritizing forms of writing that I previously—secretly—shamefully—considered not worth what little free time I have. Free-writing, journaling, collecting, annotating. I used to journal relentlessly and with deep trust in the process. Sometime around my beginning to apply to MFA programs, and definitely by the time I started graduate school, I just… quit. I've been trying to look honestly at why that happened and to open the door to that climate of writing. I can't believe how hard it has been to allow myself to write without restraint and without expectation of concrete “results.”

ET: Do you have any words of advice for young poets?

LKM: You know what’s awesome and terrifying about this question is a) the number of times a year I look up articles on the internet titled things like “Umpteen Pieces of Advice for Young Writers” for my own consumption and b) the fact that, despite the aforementioned, I do actually have some words, here. I’m interpreting “young” to mean somebody who is still figuring out their poetry practice.

In my life, reading comes before writing. I must put reading first, or there is no writing that is creative in nature. I don’t think this must be anybody else's experience, but I do recommend that you ask questions about your reading that equal the depth and hunger and courage of the questions you ask about your writing. Desire as much for yourself as a reader of poetry as you do for yourself as a writer of poetry.

. . . That said, if you’re like me and you have a tendency to use your love for reading books as a defensive fortress in which you can hole up and avoid going out into the uncertain territory of writing, and you secretly yearn to be more connected to your own creative acts, then pencil that shit into your calendar and make sure you’re making time to explore your own language, too. (And don’t let how others relate to their time dictate how you relate to yours. Sometimes people who are giving you advice, including myself, are ignorant of certain life realities that make time operate very differently for their readers. Figuring out your practice is an ongoing process that you are best qualified to outline for yourself, not anyone who is less “young” in any way.)

Remember that growth can be painful, so don’t deny yourself that experience.

Remember that growth can be pleasurable, so don’t deny yourself that experience.

***

Lo Kwa Mei-en is the author of Yearling (Alice James Books) and The Bees Make Money in the Lion (Cleveland State University Poetry Center) as well as two chapbooks: The Romances from The Lettered Streets Press and Two Tales from Bloom Books. She is a Kundiman fellow from Singapore and Ohio, where she now lives and works in Cincinnati.

Lighthouse Reading Series 2016-2017

The CSU Poetry Center is excited to announce our 2016-2017 Lighthouse Reading Series! So excited for these poets and essayists to join us; find out more here.

2016 Book Contest Results

The CSU Poetry Center is thrilled to announce the results of our 2016 book competitions. The following three books were selected from nearly 1,000 manuscripts and will be published in spring 2017. Thank you to everyone who sent us work & congratulations to the winners and finalists below.

Winner of the First Book Poetry Competition

Judge: Daniel Borzutzky

Sheila McMullin’s daughterrariums

Sheila McMullin, poet and intersectional feminist, is Managing Editor at VIDA: Women in Literary Arts and serves on the Count Committee for the VIDA Count Intersectional Survey. A community-based workshop leader, she facilitates creative writing workshops for all ages as well as college prep sessions for high schoolers. She volunteers at her local animal rescue and holds an M.F.A. from George Mason University. Find more about her writing, editing, and awards online at www.moonspitpoetry.com and follow her on Twitter @SheAPoem.

First Book Honorable Mentions: Monique-Adelle Callahan’s Exit Through the Body’s Prayer; Clara Changxin Fang’s Night Crossing over the Pacific.

First Book Finalists: Kristin George Bagdanov’s Fossils in the Making; Melissa Barrett’s Moon on Roam; Bryan Beck’s Countryman; E.C. Belli’s A Sleep That Is Not Our Sleep; Jaime Brunton’s Reclaimed; Bill Carty’s Huge Cloudy; Mario Chard’s Land of Fire; Hilary Dobel’s Hot Cognition; Cassie Donish’s The Leaf Mask; Laura Eve Engel’s I Write to You From the Sea; Jameson Fitzpatrick’s Balcony Scene; Kelly Forsythe’s Perennial; Binswanger Friedman’s The Four Color Problem; Sam Gilpin’s Spawl; Monica Gomery’s here is the night and the night on the road; Christine Gosnay’s Lossless; Anna Maria Hong’s The Glass Age; R.E. Katz’s Dark Quencher; Keith Kopka’s Count Four; Emily Liebowitz’s National Park; Grace Shuyi Liew’s Careen; James Longley’s What Cheer Heptagon; Marco Maisto’s Traces of a Fifth Column; Sara Marshall’s To Be New for the Empire; Matt McBride’s Polis; Kelly Nelson’s Crossing Thief River; Lance Newman’s The Acid Craft of Numbers; Elsbeth Pancrazi’s Bodyswap; Ann Pelletier’s Letter That Never; Nina Puro’s Each Tree Could Hold a Gallows or a House; Chris Robinson’s Air Become Sinewed; Kenyatta Rogers’s Unf***withable; Zohra Saed’s The Secret Lives of Misspelled Cities; Max Schleicher’s Exhausted by the Rest; Kirsty Singer’s Tertullian’s Daughter; Molly Spencer’s Relic and the Plum; Adam Strauss’ Braided Sand Country; Kelly Sullivan’s Sleep Music; Billie Tadros’ Was Body; Carleen Tibbets’ dossier for the postverbal/; Lisa Wells’ Prisoner’s Cinema; Jared White’s The Trolls; Candice Wuehle’s FIDELITORIA: fixed or fluxed.

Winner of the Open Book Poetry Competition

Judges: Emily Kendal Frey, Siwar Masannat, & Jon Woodward

Jane Lewty’s In One Form to Find Another

Jane Lewty is the author of Bravura Cool (1913 Press, 2013), and the co-editor of two essay collections: Broadcasting Modernism (University of Florida Press, 2009) and Pornotopias: Image, Desire, Apcalypse (Litteraria Pragensia, 2010). Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in The Harvard Review, Dusie, Lana Turner, Bone Bouquet and elsewhere. She has an M.F.A. from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and currently lives in Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Open Book Honorable Mentions: Jackie Clark’s Everything Is Always Wonderful If It Is Almost Over; Gina Kelcher’s A Great Hair Day on the River.

Open Book Finalists: Carrie Bennett’s Ghost Plants and Other Animals; Carmen Gillespie’s The Ghosts of Monticello: A Recitative; Arpine Konyalian Grenier’s Yeva Girk; Sarah Heady’s Comfort; Ann Huang’s Saffron Splash; Megan Levad’s You Are Where You Live; Beth Marzoni’s There Was During a Sudden; Tyler Mills’ Salt Mask; Nathaniel Perry’s Long Rules; Beth Roberts’ Evolvers; Heidi Staples’ A**AA*A*A; S.A. Stepanek’s Somebody, Maybe; Gale Thompson’s Expeditions to the Polar Seas; M. A. Vizsolyi’s The Common Index of Poetic Lines; Joshua Young’s Sleep Ambulance.

Open Book Semi-Finalists: John Bradley’s Infinite Past: The Life & Lice of Miguel Carablanca; Alejandro Escude’s What the Atheists Speak Of; Tyler Gobble’s Hallelujah Jars; Christopher Kondrich’s Valuing; Jason Koo’s More Than Mere Light; Teresa Miller’s California Building; Jenn Marie Nunes’ Air/Or; Stan Mir’s Three Patterns; Emily Rosko’s Weather Inventions; Alexis Pope’s That Which Comes After; Liza Porter’s Rape Register; Sarah Smith’s Negative Cape; Cedric Tillman’s in my feelins; David Weiss’ Per Diem; Kathleen Winter’ Tonic.

Winner of the Essay Collection Competition

Judge: Chris Kraus

James Allen Hall’s I Liked You Better Before I Knew You So Well

James Allen Hall is the author of the poetry collection, Now You're the Enemy (University of Arkansas Press, 2008) and has won awards from the Lambda Literary Foundation, the Texas Institute of Letters, and the Fellowship of Southern Writers. His essays have appeared in Story Quarterly, Bellingham Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, Redivider, and Bennington Review. A 2011 NEA Fellow in Poetry, he teaches creative writing and literature at Washington College on the eastern shore of Maryland.

Essay Collection Finalists: Kate Colby’s The Itch; Krista Eastman’s The Painted Forest; Elizabeth McConaghy’s Migrations; Kathryn Nuernberger’s Brief Interviews with the Romantic Past; Dustin Parsons’s Dispatches From the 51st State; Kisha Schlegel’s Fear Icons; Sejal Shah’s How To Make Your Mother Cry; Julie Marie Wade’s The State of Our Union: A Collage; Nicole Walker’s Microcosm.

Essay Collection Semi-Finalists: Diana Arterian’s Arrangement of Parts; Jehanne Dubrow’s Throughsmoke; Christine Hume’s The Saturation Project; Andy Fitch’s Garageland; Wes Jamison’s Carrion; Kat Moore’s In the Non-Light; Mariko Nagai’s Imaginary Death: A Family Memoir; Mwatabu Okantah’s The View from the Stono; Shaelyn Smith’s The Leftovers; Grace Talusan’s The Body Papers.

2016 Spring Catalog: Poetry & Prose

Our spring catalog is now available for purchase! Click the photo below to order or go to Small Press Distribution.